Now that the solar panels are perched to collect the suns solar energy, it is time to write the system up and feed our electrical needs.

I ran the wires from the panels to the battery switch, and then let my friend Bob Blood do the electrical connections. Bob Blood is an ABYC certified electrician and does gorgeous work that lasts!

The solar panels lead to the charge controllers, which then feed the battery banks. These charge controllers are by Genasun and are significantly less expensive than other brands. They are made in the USA and have a reputation for being work horses, but they don't have the fancy display screens of other brands.

Instead they have a single LED light that blinks. Slow, for ready; fast, for charging; stay, for charged; red, for fault.

The solar panels are able to feed the house bank (315 amp hours and 12V DC) as well as the electric motor bank (210 amp hours and 48V DC).

The electric motor produces its own power while we sail, up to 4 amps at 48V DC! When we need to charge up the motor bank, we simply sail on a beam reach and bring up its charge!

The solar panels are the equivalent of a trickle charge for the motor bank, but they can help float the batteries while at anchor for a long time.

On the house side of our electrical system, the biggest consumer is our fridge. The fridge is 14.5 cubic feet with a freezer section and consumes a lot of amps! With the solar panels off, the house bank will drop to 11V when the refrigerator compressor turns on. With the solar panels on, the voltage stays at 12.3V with the fridge on and 13.3V with the fridge off (in between compressor cycles).

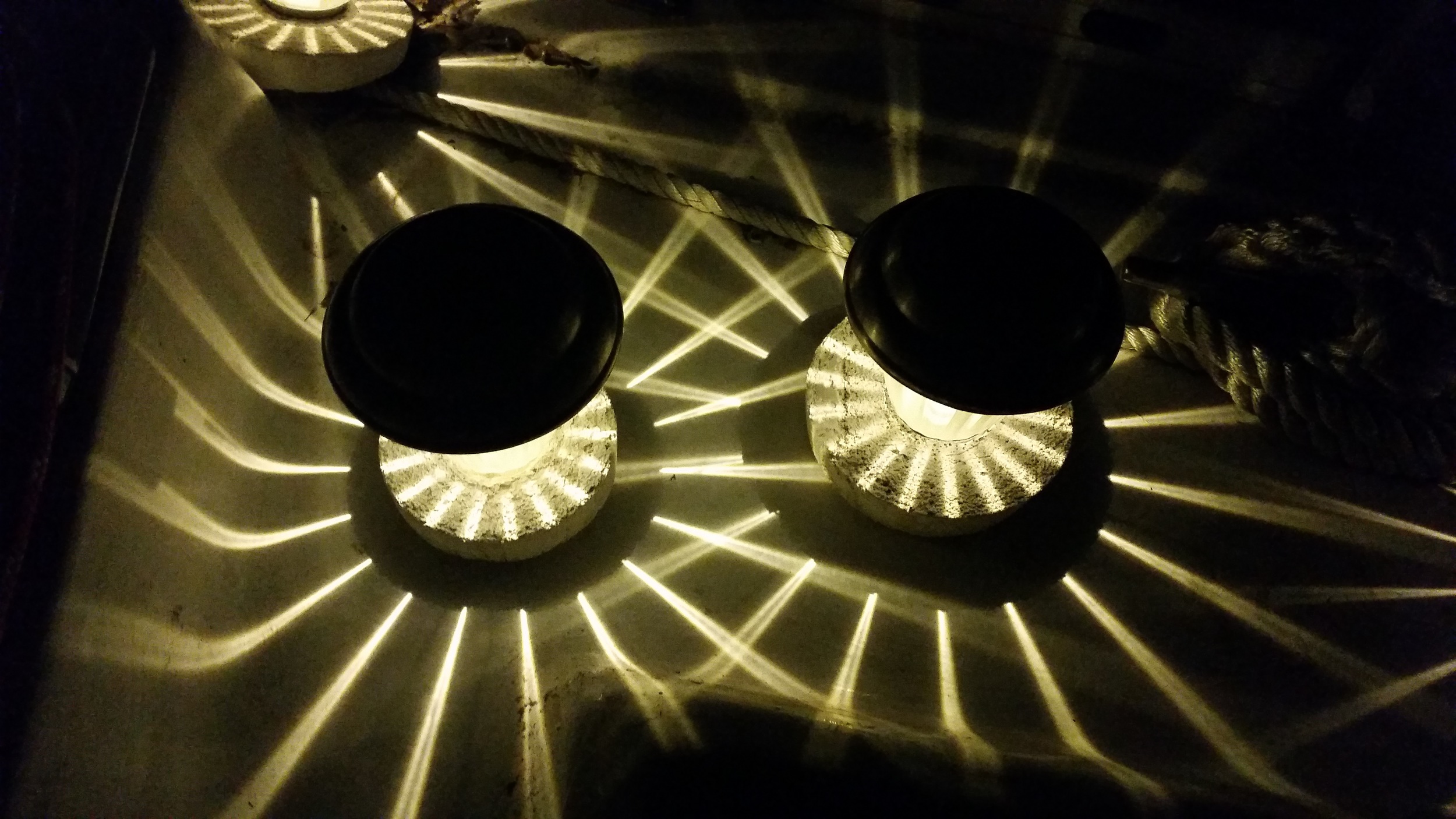

While we only have 100W of solar panels (at 12V DC), we also only have meager electrical needs. Our cabin lights and running lights are LED, and don't consume much electricity at all. Our other electrical needs are to power a small garmin chart plotter, depth sounder, and VHF radio. The only big consumer is our massive refrigerator.

By keeping the systems in the boat simple, we are also able to keep our demands low, which allows us to spend less money on solar panels to power these electrical conveniences.