Electric motors sound great, but have you ever wondered what you would do out in the ocean with an electric motor if all the wind dies?

Galvanic Corrosion on your Mast

Galvanic Corrosion is a silent killer of your wallet. It starts off so quietly and slow, barely noticed until it develops into a very expensive problem that will cripple your aluminum mast!

This mast has been pulled for winter storage of the yacht. The spreaders are neatly stowed inside the hollow spar for safe keeping. The bottom of the mast where it rests over the mast step is bubbling up with galvanic corrosion and this means that the mast is slowly but surely dying right at the base!

In a situation like this, the mast base will eventually become too weak to support the loads it is subjected to while sailing. The mast will ideally crumble down onto the mast step and all the rigging will go slack as the mast instantly becomes a few inches shorter. We all know that nothing on a sailboat breaks ideally, and instead the good aluminum just above the step and bad aluminum will slip off to the side of the step and the whole mast will come toppling down in a horrific and catastrophic failure of the rig!

For comparison, this is a perfect mast with absolutely no problems occurring at the step! Now, why is this happening to the first mast and not to this mast? Well, to put it simply, it’s because this mast is fully protected by paint and other insulating layers. There is no contact between the aluminum of the spar and any other metals, hence no cause for galvanic corrosion. The mast above must have a tiny scrape in the paint or contamination with a different metal around the mast step because the damage is localized only to the step of the mast and no further.

The damaged mast doesn’t need to be replaced, the solution is actually quite simple. The affected portion of the spar should be stripped bare and evaluated. If the corrosion is too extreme, the section is simply cut off and the mast made shorter. If the corrosion is minimal, a new coating of paint is in order to isolate the metal and protect it from further and future corrosion. Lanolin can also be used around the mast step to act as an insulator and protect against galvanic corrosion where the mast meets the step.

This mast, however is suffering from much more crippling damage.

You can see the paint bubbling up around the screw holes. This is caused by galvanic corrosion between the stainless steel screws and the aluminum spar. Apparently, no isolator was used, and if one was used, it has failed as isolating the two dissimilar metals leading to galvanic corrosion of the aluminum. The problem with this is the location.

Unlike with the other mast where the damage was located at the bottom of the spar, this corrosion is occurring on the side of the mast. If left unchecked, the side will form a hole and severely weaken the mast. This area is also in one of the highest stressed areas of the spar: The head.

All the forces of the sails, halyards, and rigging culminate at the head of the mast in the area of the truck (where all the welds are) and this is exactly where those little screws are bubbling away the aluminum of the spar. Eventually, the mast will break and make a big mess of the boat below it!

The corrosion still looks minimal and the screws do not appear overly critical. They could easily be removed and the area cleaned and protected. If they are necessary, then they can be coated in lanolin and reinstalled, paying close attention to the area in future rig inspections for any sign of renewed corrosion in the area.

If these small bubbling corrosion points are left unchecked, they can lead to very dramatic and costly results. Be sure to check any fasteners in the mast with a close eye and hold the area to the utmost standards of perfection. When it comes to your spar, there is no “good enough”!

Getting Weather Information in the Middle of the Ocean

Weather forecasts are a wonderful thing, they can tell you if it will rain or be hot out, but they aren’t perfect. How many times do you see 50% chance of rain? That’s the same as saying: “it might rain today, but it might not”.

The problem with forecasts is they are being fed to a very large area and each individual area in the larger region might not actually have the same weather as the forecast. The best way to get your local weather is to figure it out yourself. This is not going to be a “broad forecast for a large area” but instead a “targeted local forecast for your immediate area”.

The best part about this method is that it doesn’t require you to have a connection. You know all those weather apps on your phone, if you don’t have internet access, you don’t have a forecast. When you head offshore, there is no signal and no reception. Your options are to either pay a lot of money to receive satellite internet or to produce your own weather forecast from your own observations.

All you really need to accurately determine what winds will come your way are a barometer and a weather eye.

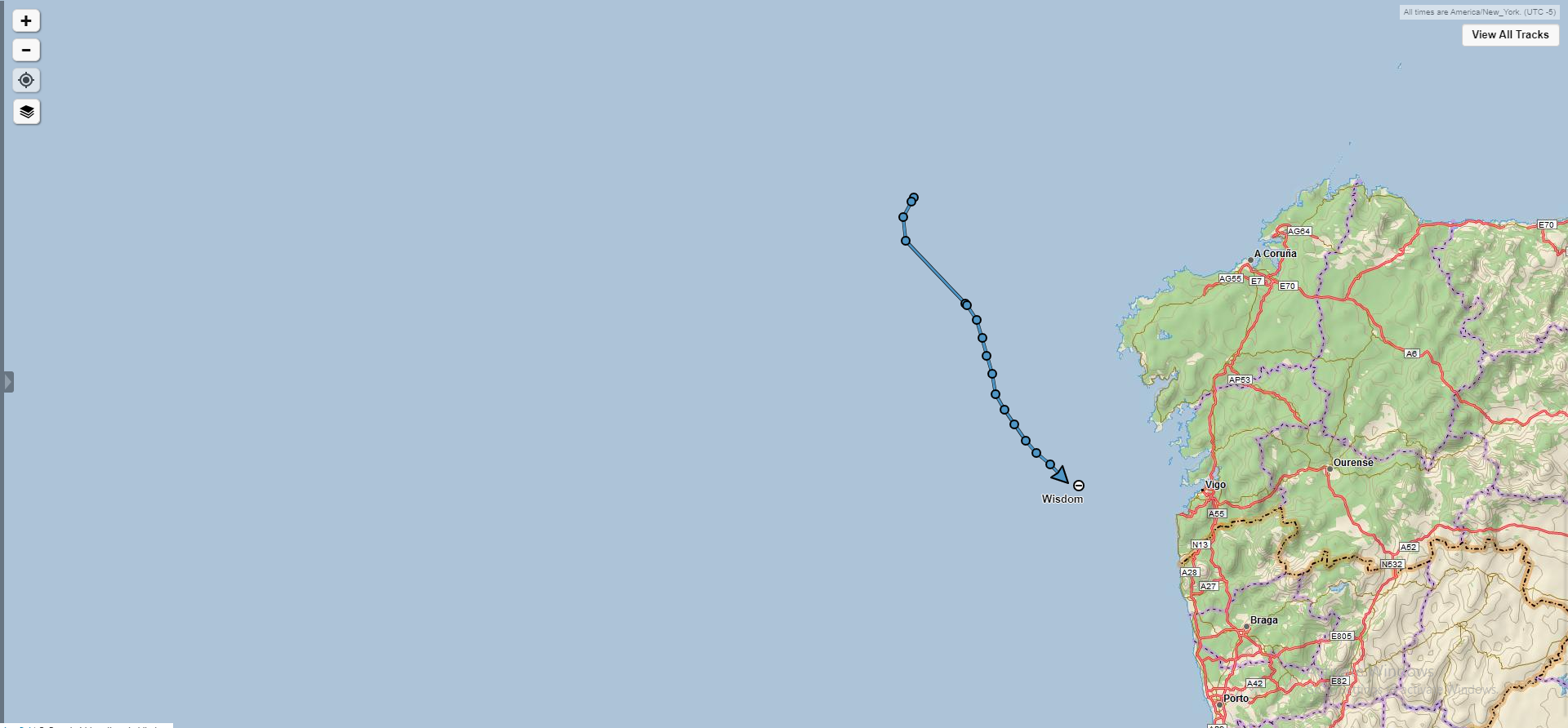

Transatlantic: Azores to Portugal: Day 19 [Day 67]

July 1, 2019 and we finally see land, even better, we TOUCH land!

Our last day at sea was incredible! The wind was behind us and slowly building allowing us to sail incredibly quickly in the still relatively calm seas. Without the waves stealing our movement in an up and down direction, all of our speed can be spent shooting forward at great numbers (for our boat).

With the weather system North of us and approaching, we were trying to outrun the clock. and make it into port before the weather got really nasty! Normally, when we see a system like that on the horizon, we drop the working sails and raise the storm sails. Then we sit and wait and when the storm finally makes its way to us, we are ready. The storm rages and then passes on by with us comfortably floating in the ocean. The thing that was different is we were very close to land at this point and reasonably able to make it to port before that storm system reached us!

For this reason and this reason alone, we did not reef. We actually remained full sail well past the time that we would normally have had those sails up. The old expression of “Fly as much sail downwind as you would be willing to fly if you were going upwind” was being grossly ignored.

The idea is if you are in 25 knots of wind and moving at 5 knots, if you are going down wind the apparent wind will be 20 knots but if you are going upwind the apparent wind will be 30 knots. There is a huge difference between 20 and 30 knots and therefore a huge difference in the sails you would be flying for these two conditions.

We kept the sails up for as long as we felt was stupid to keep them up until I had the main eased all the way and were still overpowered while on a run. I went forward and tucked in two reefs with a full belly and a loose outhaul to keep the speed up along with the control of the boat. When running downwind with the mainsail far out, the boom acts as a lever arm trying to turn the boat to windward. Reefing helps alleviate this issue as the sail becomes smaller and closer to the middle of the boat instead of out on the end of the boom.

We screamed along in the calm following sea, watching the waves slowly build as we scooted our way towards shore in preparation for our arrival. When we finally got there, the tide was just beginning to fall and the winds were light in the marina. We were able to sail in through the breakwater and come into the marina under sail. We lowered the sails at the last possible moment and used our electric motor to bring the boat into her slip.

Our long voyage across the North Atlantic Ocean is now complete! We made it!

Transatlantic: Azores to Portugal: Day 18 [Day 66]

The trade winds are present and we are moving at speeds and comfort like we have never moved before!

Day 18 and still no sight of land. The date is June 30, 2019 and we are almost there!

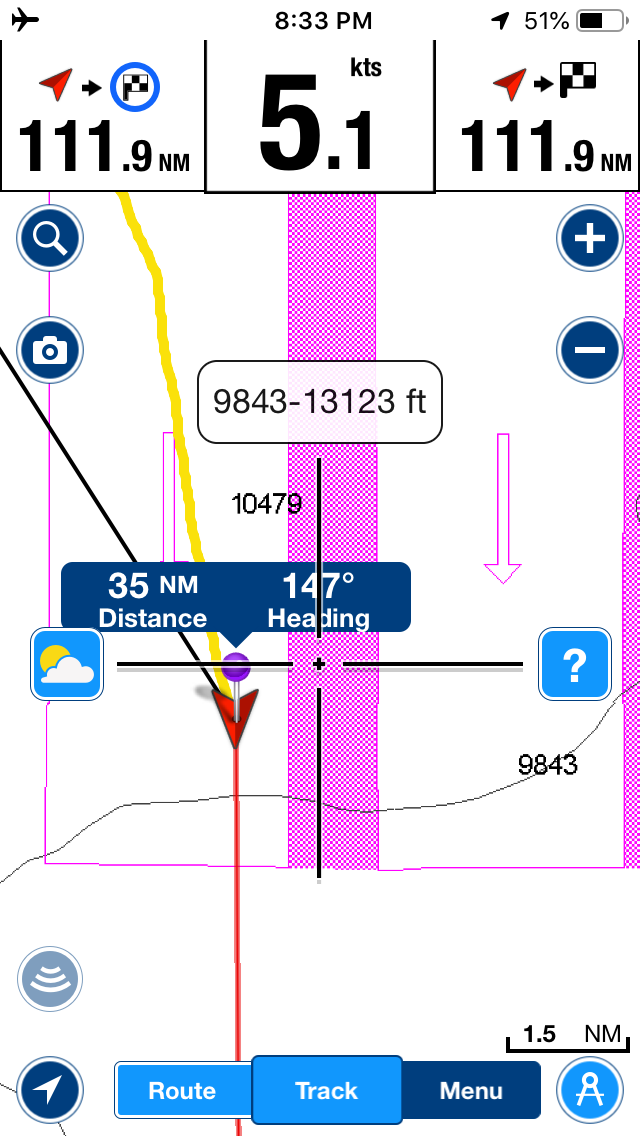

The trade winds seem to be stronger near shore, which means that the close we get to shore the stronger the winds will be and the faster we will be moving along. All was fine with our course until we came across a separation scheme off the northern tip of Spain. All the traffic coming out of the Mediterranean and bound for the English Channel will want to pass close to this point of land. That means that there is a lot of ship traffic and as a result there is also separation lanes dividing Northbound ships from Southbound ships.

The problem is we want to cut closer to land so that we don’t get swept away by the current and miss our harbor, but our course had us cutting right across the lanes! We sailed along in the outermost Southbound lane and once we were clear of the separation scheme and there was space between all the cargo ships, we cut along towards shore where we could be certain we would not miss our destination.

This might be our last night out at sea on the open ocean for a while, so we took special care to appreciate the sunset we were presented with. While it is beautiful, it forewarns of winds to come.

You can see that we are in a cloudless area with a relatively high pressure. The sky is clear until it reaches the wall of towering clouds in the distance. The red hue on all the clouds is caused by the refractive lens of the high pressure we find ourselves in, making everything we look at in the distance display a "red shift”.

What this tells me is that we have calm and wonderful conditions at the moment, but that will change when those clouds approach. The base of the clouds is not visible which gives some clue to their distance away. The bottom of these low level clouds tend to be around 3,300 feet above sea level. The bottom becomes visible when the clouds are about 100 miles away. The tops of these clouds can reach 60,000 feet above sea level, which can be seen from about 300 miles away. Being how we see the tops and not the bottom, we can assume that these clouds are somewhere between 100 and 300 miles away from us!

The clouds billowing up into the sky demonstrates great atmospheric instability over there and it is all occurring in a line. This means that when the cloud line approaches, the winds will jump from calm to insane in a hurry so we need to prepare ourselves for this wind before it arrives (or make it to our port before it gets to us).