Part of the construction process of our new dinghy involves some metal fittings that need to be custom made to fit the hull. The choice of metals was simple since we are building a wooden row boat, and as such, the only metal that should be found on such a woody is bronze!

Bronze is an ancient metal, famously characterized by the Bronze Age which started around 5000 years ago! Since this metal was first worked by man with 5000 years less of technological advancement, I figured that this would be an easy task to carry out.

My first plan was to cast plates of bronze that will cover every corner of the dinghy. This means that I need plates to cover the chines, garboard, transom, and stem. I built a foundry, borrowed a propane torch from my brother in law, and picked up some steel molds that would make a nice shape for the bronze plates.

The molds are 5 inches by 7 inches, and would easily fashion out some bronze plates that should be exceedingly thin. I would then take these thin plates and bend them to shape over the hull where they would at last be fastened into place.This was at least the plan, but far from the reality of how things would progress.

Yes, technology has progressed to the point that some kid can make a foundry in a bucket and heat bronze ingots to over 2000F in his back yard. Technology has not progressed to the point where this would be easy though! Each ingot takes around 30 minutes to melt. If I were to make all the bronze plates to cover everything as planned, I would need to make around 60 plates, consuming 30 hours of melting time!

Obviously this is not going to be practical, so I instead looked at the critical areas that actually need to be covered in metal plating. This would be just the stem, as this point will be subjected to the most stress and punishment through its life.

Heating the metal was pretty mindless, all you need to do is light up the forge and let it burn. Casting was a whole different animal!

My first attempt at casting was into the steel mold. I figured the molten bronze would run all over the mold and lay flat, filling the bottom of the pan similar to water before cooling into a solid again. What really happened is the bronze hit the cool pan and started to solidify instantly.

This created a small blob in the middle of the mold, far from a clean plate. I attributed this failure to a few key points:

The mold was not hot, so the metal cooled too quickly on contact.

The mold melted a little where the hot bronze was poured in, allowing it to pool thicker there.

There was not enough bronze to cover the entire mold, leading to my lack of filling.

The cold mold would be addressed in my second attempt, along with the mold yielding under the heat, but the amount of bronze was still a problem in my mind.

I want to create a thin plate that will easily be bent over the chine. If the bronze is too thick, I will not be able to bend it, thus it will not be useful to me. By pouring more bronze in, I am instantly creating a stiff and thick piece. In my mind, adding more bronze is not the answer as it will create a problem in the cast plate.

I made some changes with my second attempt, making the mold for the plate out of Plaster of Paris, which should hold its shape during the casting process and not yield. I also set the mold over the exhaust of the furnace to heat it up, giving me more working time as the bronze was poured in. Lastly, I gave in and melted down twice the amount of bronze as my first attempt, hoping that it would be enough to cover the entire mold in a thin plate (ideally less than 1mm thick).

The foundry was fired up, and a half hour later I was ready to pour the molten metal into its shape! At this point, I would continue to learn that ancient man was really impressive to cast their tools in bronze!

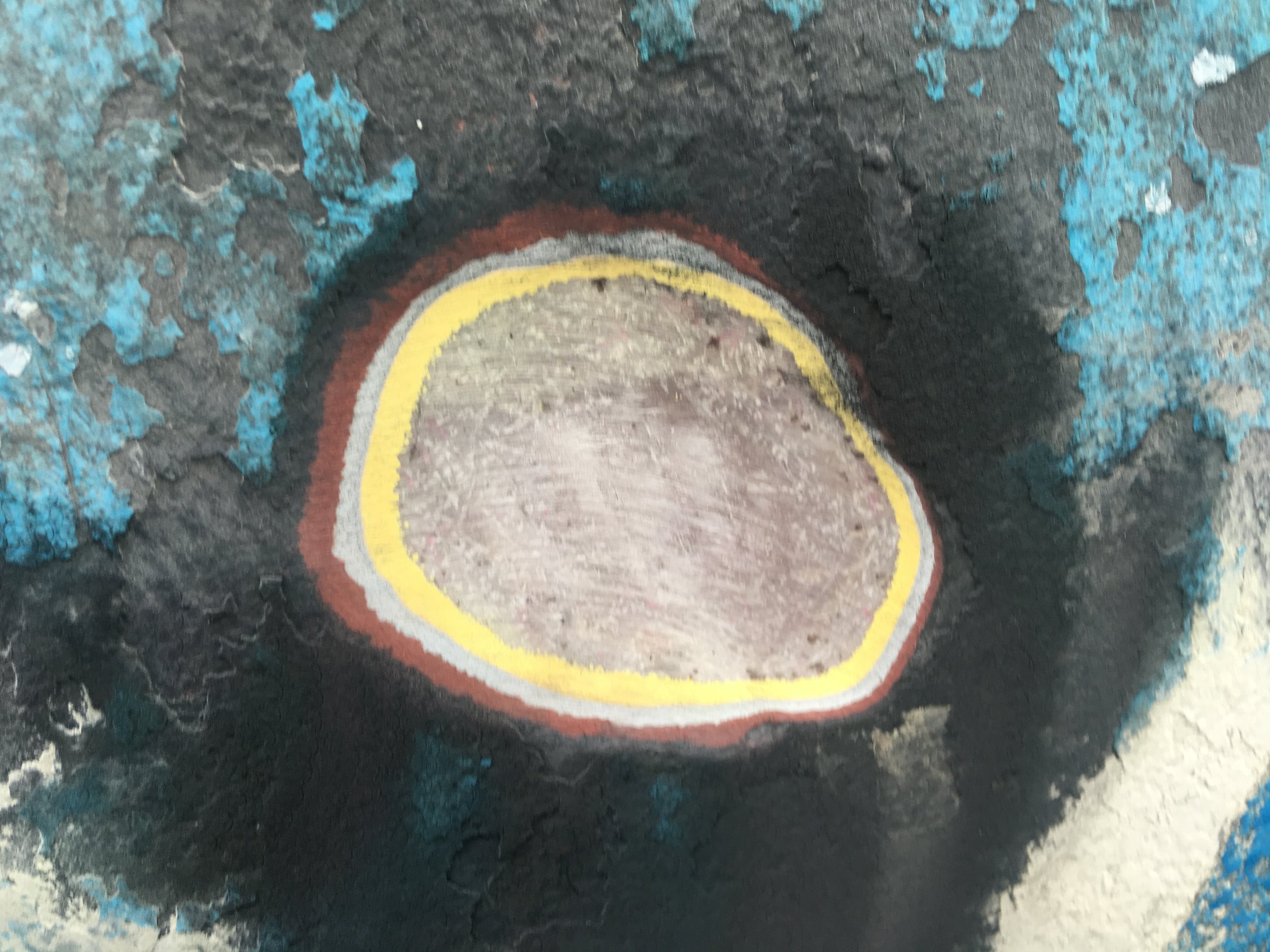

I poured the metal into the stone mold and it failed once again. The metal still cooled too quickly as it entered the mold, creating a very rough surface which would not work as a plate. Secondly, the mold was slightly tipped, so one side was thicker than the other. Heating the mold on top of the foundry provided no additional working time, just disappointment.

The second attempt was only 3mm thick, and covered only 3/4 of the mold. While still very thin, the metal is so strong that I can not bend it with ease. This means that it would not bend over the chine like I would need it to, and instead, it would just break the dinghy as I tried to muscle it into place.

I have concluded that pouring bronze into an open mold will not serve my purposes and instead I will have to resort to the "Lost Wax Technique" to cast the pieces in the final needed shape that will fit the dinghy.

Attempting to cast bronze has been a huge wake up call. People often think that they are better than ancient man because they have smart phones and airplanes, but the truth is, ancient man laid the foundation that we have since built upon. The skills they invented were by no means an easy task, and re-learning them is still a tricky set of skills to master.

Yes, I can easily look up on the internet how to melt bronze and how to make a mold, or how to pour a casting. What the internet won't tell you is how incredible the people who pioneered this technology were.