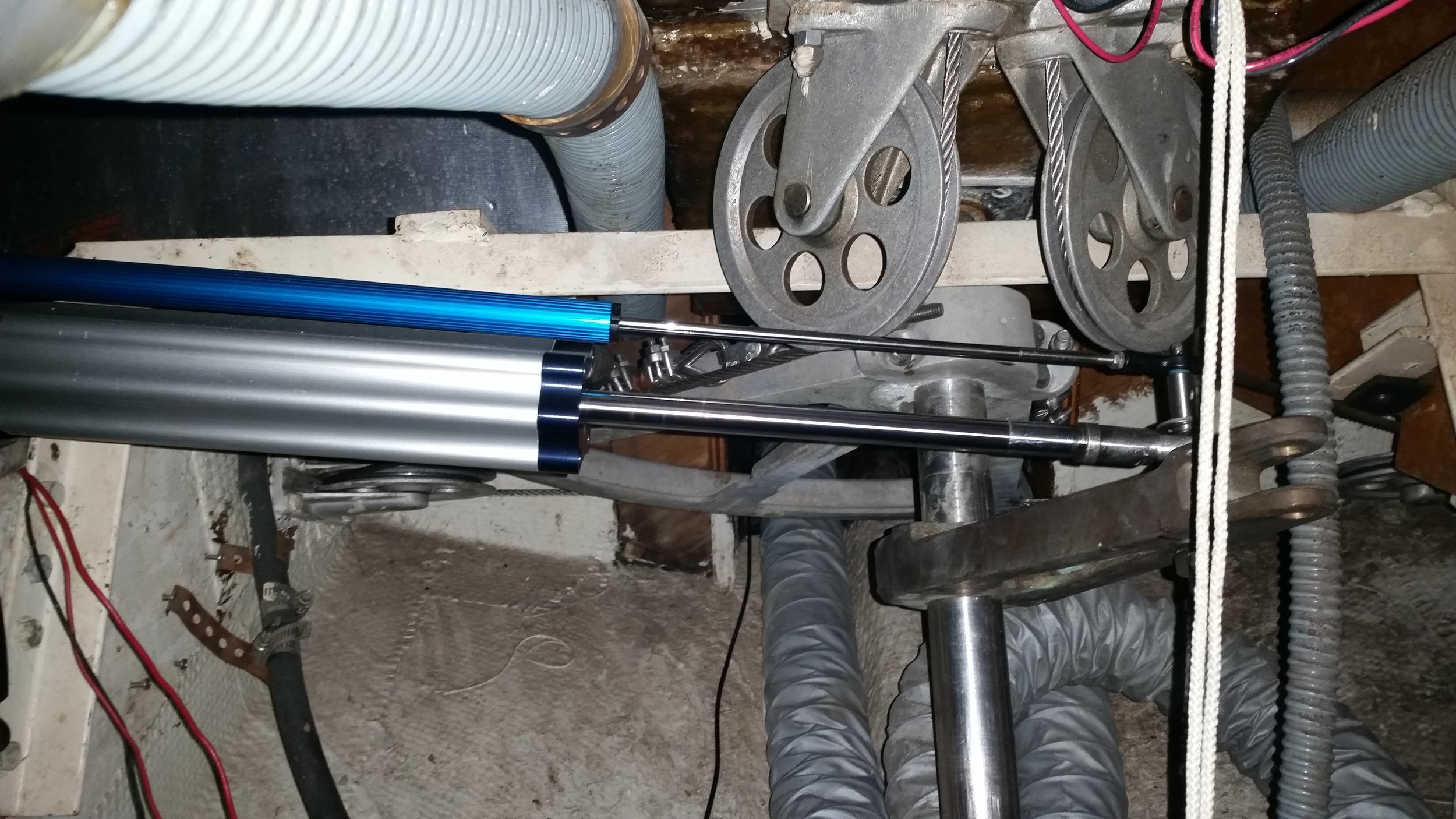

$4,000 and a lengthy installation later, we had the unit in the boat and ready to run! The unit sits below the helm and connects directly to the rudder post via a bronze tiller arm and the display unit was attached to the binnacle. The final installation looks very clean and neat, all the wires are hidden and out of view. When you hit the button, the wheel will begin to move as if the boat were being steered by some sort of magic!

The wheel would move slightly to port, then slightly to starboard, then back to port, and then back to starboard. The wheel keeps moving all the time! Each motion of the wheel causes a drop in voltage as the unit drains the amps out of the battery, soon our battery bank has been depleted and the unit must be shut off.

I quickly began to browse through the settings of the unit, discovering that there was an entire setup which I had skipped! After running through the settings and completing the setup, I got the unit dialed in and set up for our boat, and it behaved much better. The steering wouldn't overcompensate as much as we found ourselves able to run it for longer, but not as long as we had hoped.

Each time the wheel is turned, amps are consumed. Making the wheel turn less often simply means that the amps will run out later rather than sooner, but they still run out and the unit needs to be turned off. The solar panels help power the autopilot, but only while the sun is shining. If a cloud passes over, the voltage will begin to drop until the skies clear up once more.

Every time I turn on the autopilot to steer us for significant distance, I find myself tending to the solar panels to angle them so that they produce the most power possible for that time of day instead of relaxing. I then sit on the throne where I can keep an eye on our voltage instead of relaxing on the bow where I want to be. Since I have yet to leave the cockpit area, I have yet to use the remote control which was the entire selling point of the unit!

The one situation where I find the electronic autopilot very convenient is for sail changes when I am alone. I used to struggle with the "Sail Shuffle" where I would run back and forth from the mast to the helm. I would set our course and lock the wheel and run up the the mast and begin raising the sails. As the sails would come up, the balance would shift and our course would change, forcing me to run back to the cockpit to adjust our course, then back to the mast to raise the sails more, then back to the cockpit to adjust our course again. After five or six trips back and forth, the sails will be raised and we will be on our way. Reefing was even more interesting! Imagine doing this shuffle with high winds and tall seas on a boat that is being overpowered and in need of reefing!

This one situation is where the autopilot shines like the Polaris, the North Star, giving you guidance on the darkest of nights. I simply hit "Engage" and the autopilot takes over. There are no strings to pull or settings to trim, simply hit a button and the computer will take over from there. As the sails go up and the balance changes, the autopilot will turn the helm to compensate. While the unit will consume a significant chunk of power during this ordeal, it is worth it! I don't have to worry about jibes or veering off course while I'm busy working the sails. Once they are raised, I can run back to the helm, shut the autopilot off and take over from there.

$4,000 later, we have an electronic autopilot unit that we don't use for long distance cruising, only for short moments where we need an extra hand at the helm. Being how a good self steering unit is very convenient for long passages, we have decided to bite the bullet and purchase a wind self steering system.

$6,000 has been set aside for a Scanmar Monitor Windvane which I will pick up at the Annapolis Sailboat Show in October. This unit will sit on the transom and keep our boat on course relative to the wind without any electricity required.

I began thinking back on why people favor the electronic autopilot over a wind vane system, and the only conclusion I could come to is: People don't sail.

Since people don't sail, the practice of balancing sails may seem foreign to them. Since they can never get their sails to balance, they also can't get their wind vane to steer properly. An electronic autopilot will work harder, but still maintain the course even if the sails are not perfectly balanced. The idea of pushing a button may seem more familiar to the general boating community and therefore must have been better received over the strings that need to be pulled to activate a wind vane.

Lastly, since most sailboats motor everywhere, they have plenty of electricity on hand to run an electronic autopilot. If their voltage begins to drop, they can simply crank up their engine and meet all of their electrical needs. I do not have this luxury, as we have an electric motor.

Being how we sail everywhere and balancing the sails seems second nature to us, I feel we will greatly enjoy the Monitor wind vane.

Looking back on my past choices, if I had to do it again, I would have simply saved up a little more and paid for a Monitor wind vane instead of the electronic autopilot. $4,000 is quite a chunk of change to spend on an accessory that I only use for a few minutes a day, even though it is rather convenient when I do use it.

I think the best way to plan to power your self steering gear is to use the same power source that you generally use to run your yacht. If you use fuels to power your yacht, then fuels would be the ideal power system for your self steering. If you use wind to power your yacht, then wind would be the ideal system for your self steering.

Fuel could be gasoline, diesel, or electricity; and if you use this to power your vessel the majority of the time, then an electric autopilot would be your preferred method of self steering.

For those who use wind to power their sailboat, adding one additional sail to trim won't add any great complexity to their yacht. We trim our sails with sheets and control lines, just as we trim the sail on the wind vane using control lines. Having a firm understanding on how wind works to power your yacht through the seas will let you also feel comfortable using a wind vane that is trimmed to a certain wind direction and will keep your yacht sailing on a course relative to the wind.

In the end, we will have spent around $10,000 on self steering equipment. This will give us the flexibility of using both types and having the ability to use whichever one is more convenient at the moment, but this is an expensive price to pay for the ability to ask yourself "which self steering do I feel like using today?" If I were to do it again, I would choose a wind vane system.

This choice is not based on first hand experience with a wind vane system (yet!) but because I know from experience that an electric autopilot system is not a good fit for our yacht which relies on wind to power it forward.